There may be a time in my life when I am embarrassed by the choice to write this, but right now I’m embarrassed about not having written it sooner, so here we go.

The ancestral makeup that generates my skin tone is one half Irish/Scottish (there was some debate among family members) and one half Mexican/Hungarian. I have a fair, sometimes ruddy complexion that burns quickly, freckles, and generally doesn’t get along well with the sun. And for years I’ve avoiding identifying with this, the largest organ in (on?) my body, because of the story I assume you think it tells about me.

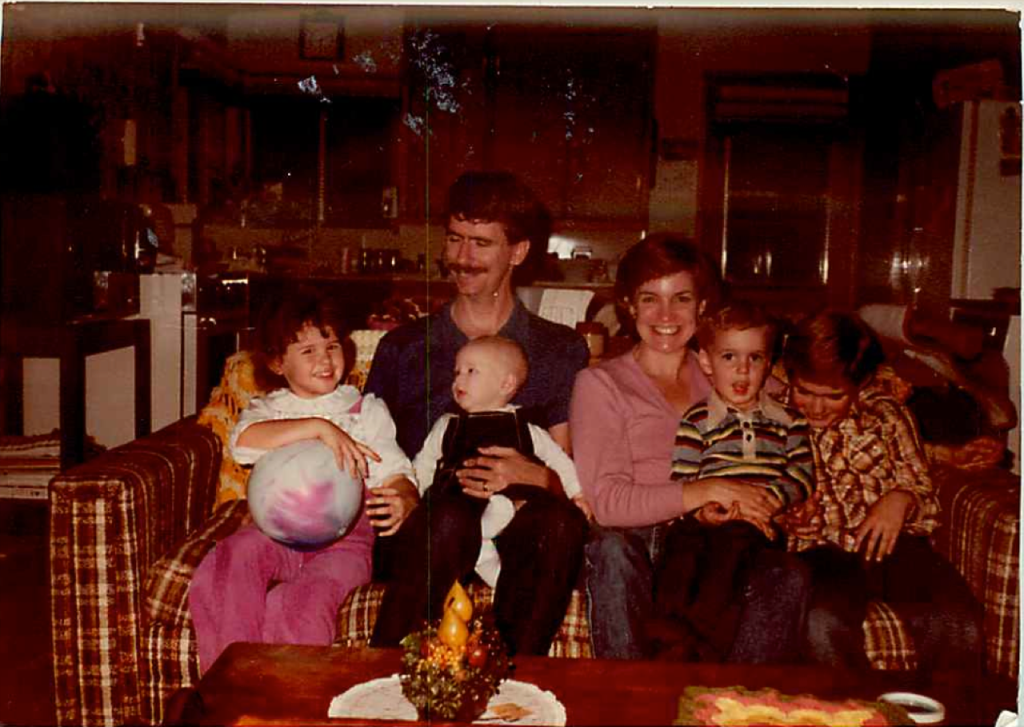

this white baby is me

I grew up in a medium sized suburban city (Orange) in the middle of a very conservative county (Orange) in Southern California. And it was there that I learned to dislike “white people.” Now, let me be clear… my dislike of “white people” has little to nothing to do with an entire race of people (and much more to do with the mainstream culture of my town) and has even less to do with my beliefs about whiteness now (we’ll get to that). It was instead, just a good ol’ cognitive distortion, assembled with experiences to create a series of beliefs like:

- I don’t like “white people” because they value sameness, and I feel different

- I don’t like “white people” because they keep their emotions tucked behind a firm layer of social nicety, and I want to shout everything I feel aloud

- I don’t like “white people” because they go to church where – based on the few times I was dragged along – the main event was sitting still for an hour and hearing about being unworthy, and I… well, I just don’t like that

- I don’t like “white people” because they vote republican, want to keep all the money they make, and are quick to judge others as lazy, and I see systemic inequities (I didn’t know those words then) and want to help

- I don’t like “white people” because they’re boring, and I (even though I am) don’t want to be

In other words… I don’t like “white people” because I don’t think they like me, and I’m all for pushing others away before they can leave me.

My two sets of grandparents, all living at the time (and now down to just one of four), were the embodiment of this division I saw in the world and felt within me.

this adorable white family is mine (and everyone in this photo is a lovely individual)

My white grandparents lived in a 2 bedroom, manufactured home in the Joshua Tree Desert. They had a huge satellite dish on the side of the house that brought in, what felt like, 3 channels. There was also a shuffleboard court and a swing outside, a remote control toy General Lee, an organ, and an autoharp. And it was quiet. Both of my grandparents were soft spoken. I never heard either of them raise their voice. They went to bed early and woke early. My grandma made us pancakes with club soda in them which made them light and fluffy. They had Corelle dishware. They wanted to hear me play the organ (or my clarinet, or saxophone). They wanted to play a card game with us. They wanted to hear about our days. They showed up to all of our performances. They came to be with us for all the holidays. They are what I know now to be idyllic grandparents, and I would do anything to go back in time to be with them and appreciate them, but I was bored.

The other side of my family is where the action was. My Hungarian grandmother’s Mexican husband had died years before, but the 6 half breed children they’d had who were now adults are where I identified with my Mexican roots. My grammy and her husband (a retired police detective with some loose genealogical ties to Edgar Allen Poe, white – but famous) lived in San Clemente in a 2 story house just a couple blocks from the beach. There wasn’t much of a yard, but inside the house was a maze of rooms, nooks, crannies, and places where treasures were stored. There were pink depression glass dishes we weren’t really supposed to use, but did anyway. Up the dark, carpeted, floating stairs my grandpa had a collection of clown paintings and figurines that were classically creepy. And there were always people around. Loud people. Arguments. Food. Drink. Drama. Showing up for and being concerned about me was limited at best. There was plenty to want for. It was dramatic. It was, in retrospect – not particularly healthy, awesome.

And so my beliefs about race, including my own, were cemented. “White people” were boring and I didn’t want to be one. “Brown people” were exciting and I wanted to be seen as one.

The issue with this is that I didn’t have much brown people cred. First, my skin wasn’t brown. To get a tan I would have to diligently avoid burning by religiously applying 80 spf sunscreen multiple times a day while spending at least 8 hours in the direct sun daily for at least two weeks. I also didn’t speak Spanish. Not even Spanglish, which I’ve since picked up.

Then in Jr. High, Stephanie Knecht, whose blond bangs were sprayed to an impressive 5″ height, furrowed her overdrawn brows at me as she shoved me into a locker and accused me of “mad dogging” her. Stephanie, the resident white girl that hung with the cholas, was my lily white ass’ only potential in with the crowd I supposedly identified with… and that didn’t work out. So, I just gave up figuring out who I was, or what I was and stopped thinking about it.

I intentionally distanced myself from the community I grew up in (by the way, my parents were totally lefty liberals… I guess they just thought suburbia was safer) and sought out a feeling of belonging elsewhere. A bunch of other dramatic stuff happened that is irrelevant at the moment, but I’ll write a book some day.

When I started working in Diversity & Inclusion a few years ago, the question of my racial identity came up again. No one asked me outright, but I assumed it was the question on everyone’s mind (for the record, I have NO idea if it actually is/was). In response to the fear of in-credibility (<– if that word does not exist, it should) I played up my most “diverse” dimensions. I got an asymmetrical haircut with a shaved side to be more visibly queer. I started wearing an Our Lady of Guadalupe and darker lipstick any time I was facilitating a diversity training to give hints at my Latin/Catholic heritage. I stopped wearing cardigans over my flabby arms to make sure everyone knew (who didn’t) that I was also a fat person. I debated changing my last name to my mother’s maiden name (which I won’t tell you because it’s the answer to so many security questions).

still white. even with this badass haircut.

It turned out all of my worries were for naught. I’m good at my job because I’m good at being in a state of learning and moderate discomfort. And the diversity cred I perceived I needed to be taken seriously hasn’t been an issue partly because I work within a framework that heavily emphasizes honoring ALL dimensions of diversity (beyond race, ethnicity, gender, age, and sexual orientation) and expects/allows for self identification of all dimensions. I still worry, though, but mostly about other things.

And then Alton Sterling and Philando Castile were shot.

And instead of turning away, I looked. I watched. I read. I listened. I did not push away the hurt. I did not push away the discomfort. I dove in and I learned something important: I am white.

In the 30+ years I spent trying to distance myself from my perceived (insert: actual) race I was missing a BIG piece of the puzzle.

While I still, and will likely always, value the dignity that comes with inviting someone to self identify, and I still struggle with the reality that race (a mere social construct) has so much weight, I will never again discount the truth that race matters and perception is reality. I may not feel like a “white person” (based on the beliefs I had about white people when I was child which have since been discredited through the process of maturity), I LOOK like a white person, and that’s what matters. Because looking like a white person is a privilege.

White privilege is likely, at least in part, why I have been offered jobs, been approved for rentals, been able to shop in peace, been able to sass the police without any harm befalling me, been granted social niceties, and generally been kept safe, lifted up, encouraged, and celebrated by the communities I engage with. Everything I wrote about in this piece, and likely more than I have even realized, is a function of white privilege. Wondering about my race is a privilege that people of color do not have the option to do – the world gives them PLENTY of information about their race and what it means about them. Changing my appearance to convey different messages about myself is a function of my privilege – my skin color, the foundation of my physical appearance ensures I will convey “safe” to most people who cross my path no matter what my hair or makeup look like. Even writing this, expecting it will be read, and the likely reality that no harm will befall me because of it is a function of my privilege.

And I didn’t realize until all too recently… that by trying to distance myself from my whiteness, what I was really trying to distance myself from was feeling guilty for my privilege.

I am sensitive to inequity. I can’t help but see it and I want it to go away. And somehow within my childlike mind I was successful in doing the mental gymnastics I needed to do to safely distance myself from taking responsibility for the parts I play in maintaining the systemic inequity society is entrenched in.

White guilt is an easy next step once you’ve stumbled upon the truth of white privilege. I am hoping to skip over it, but the truth is I’m on shaky ground and I don’t know what will happen. The first feeling I had when I truly allowed myself to witness the depth of the injustice people of color live with daily was anger. I am not comfortable with anger, but I knew it had a message for me so I sat with it. And what anger taught/reminded me is that I am not effective when I am angry. My gifts are compassion, forgiveness, humility, and kindness. When presented with the question: what gifts do you have that you are not using? My answer was: all of them. Time to change that up.

Right now, I believe that the most important thing I can do as a person of privilege is use my privilege to create safety and space for people of color. I can close my mouth and listen to people of color. I can use the safety my privileged appearance inspires in other white people to gently influence perspectives and behavior change.

When I see inequity, I do something.

When I witness a microagression, I do something.

When I hear racism, systemic or individual, I do something.

When I have an opportunity to educate, I do something.

When I am asked to help, I do something.

Even when I am not asked… I do something.

—–

“If you are neutral in situations of injustice, you have chosen the side of the oppressor.” – Desmond Tutu